BRAF hosts Essie Chambers winner of Ernest J. Gaines Award for Debut Novel

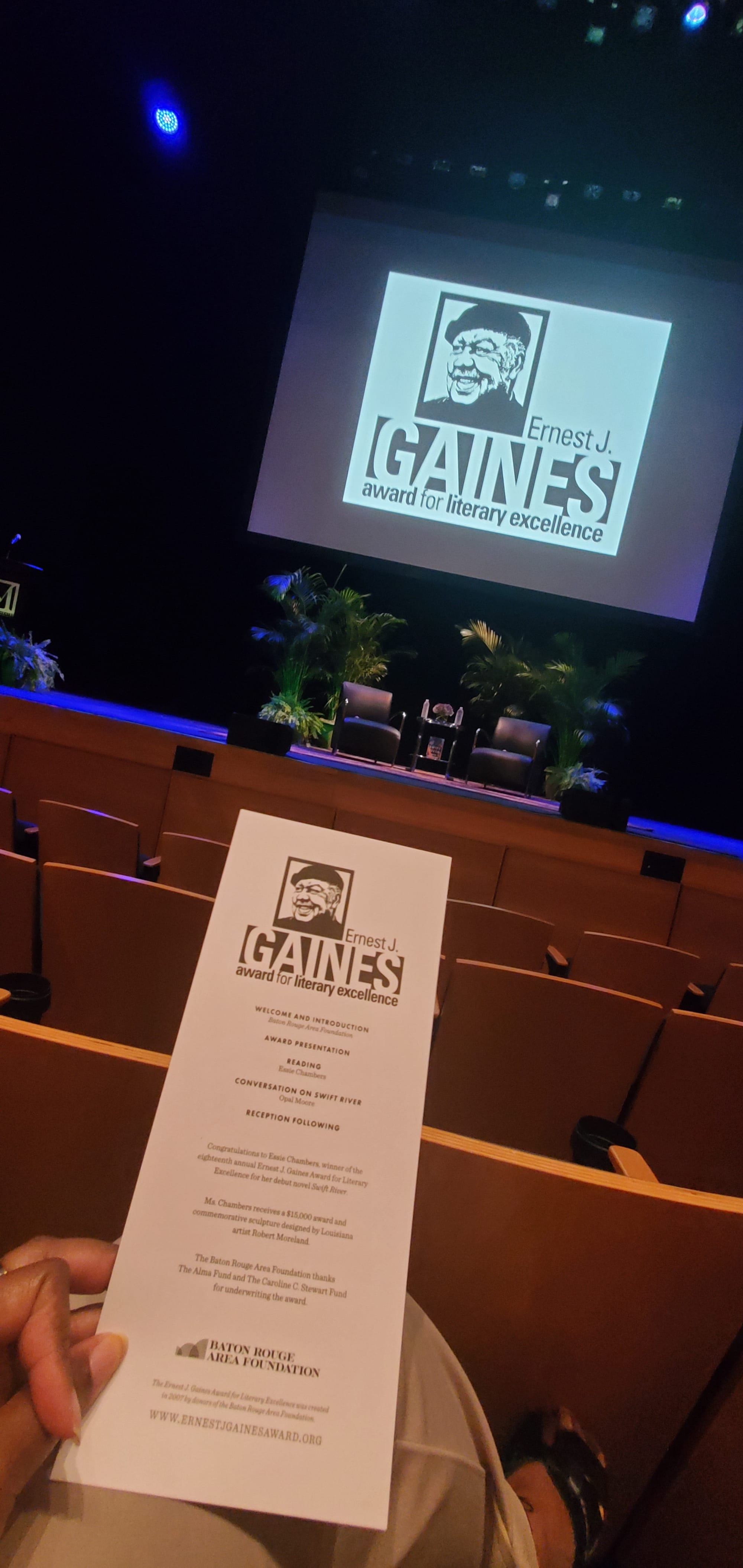

The award, presented by the Baton Rouge Area Foundation, honors emerging Black American fiction writers and carries a $15,000 prize.

At a Baton Rouge ceremony, the author of “Swift River” reflected on racial isolation, ancestral storytelling, and the literary inheritance that shaped her voice.

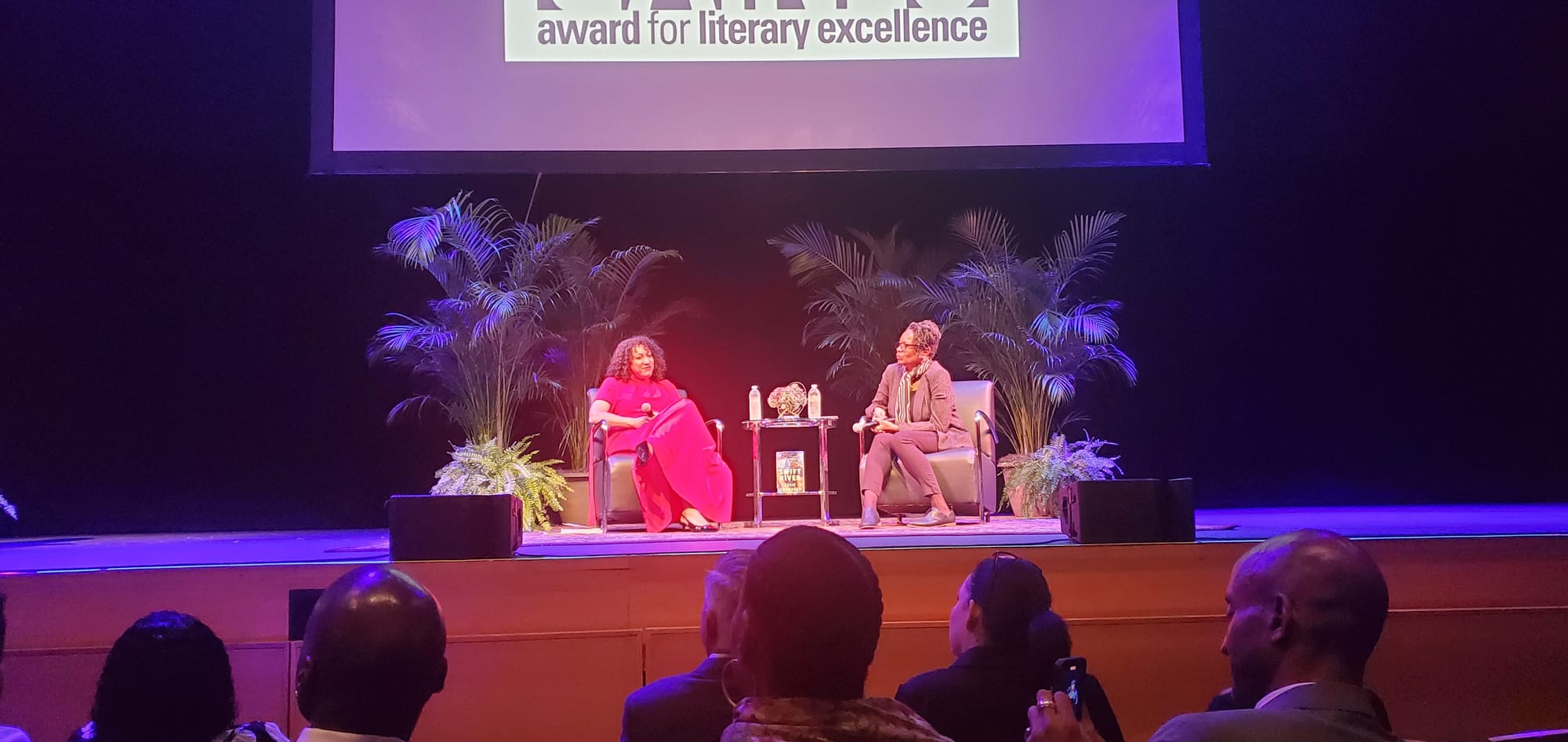

On Thursday, Oct. 21., in the warm hush of the Manship Theatre, novelist Essie Chambers stepped to the podium to accept the 18th Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellence—a prize she described not as a destination, but an act of connection.

The award, presented by the Baton Rouge Area Foundation, honors emerging Black American fiction writers and carries a $15,000 prize. Chambers was selected for her debut novel, Swift River, a lyrical and layered coming-of-age story set in 1980s rural New England, where a 16-year-old girl begins to piece together a fractured family history in a town that has never fully welcomed her.

In her remarks, Chambers spoke of her path to writing—and of how, long before she read Gaines, she watched her father as he read Gaines novels.

A Debut Ten Years in the Making

Swift River was a decade in the making, Chambers said during a post-reading conversation with poet Opal Moore.

"Mr. Gaines' gaze upon Black life is unflinching, but never without tenderness," Moore said, "It is a privilege to sit here with Essie Chambers tonight, honoring the legacy of Ernest J. Gaines in the work and the spirit of a young Black woman writer who honors such complexity in her debut novel."

The novel centers on Diamond Newberry, a mixed-race teenager navigating life in an overwhelmingly white New England mill town where her father disappeared seven years earlier. As Diamond begins to receive letters from relatives she’s never met, her personal story unfolds alongside a deeper reckoning with generational silence, racial exclusion, and the ghosts of family left behind.

Chambers described her own upbringing in a similar New England town—one of very few families of color in the community—as the emotional foundation of the book. “We were isolated,” she said. “We had friends. We were involved. But we didn’t have Black community.”

That dissonance—of being visible but not seen, included but not understood—became the psychic terrain of Diamond’s story.

“I’m drawn to outsider stories,” Chambers said. “To characters who feel like they have to fold themselves in half just to belong. I wanted to explore the spirit damage of that.”

The novel unfolds against the backdrop of a crumbling industrial town where the mills have shut down and the river that once brought work now carries only memory. In that setting, Chambers said, she saw a way to weave together loss—of labor, of family, of identity—with something more elusive: the possibility of return.

History, Haunting, and a Hidden American Geography

While researching the novel, Chambers began looking for evidence of Black communities in rural New England during the early 20th century. She found little. But her research led her to James Loewen’s Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism—a book that would reshape her narrative.

Sundown towns, she explained to the audience, were places where Black people were forbidden—by law, violence, and custom—from remaining in the town after sunset. She had always associated such practices with the Jim Crow South.

“I was shocked to learn that sundown towns were largely a Northern phenomenon,” she said. “New England, the Midwest, the Pacific Northwest. It shifted how I thought about place—and about which histories we allow ourselves to claim.”

From that realization emerged Clara, Diamond’s great aunt, a young Black woman who chose and was allowed to stay behind in a Northern sundown town after others were forced out. Clara’s story is told in recovered letters, written decades earlier, that ultimately bring Diamond closer to a lineage she didn’t know she had.

Chambers said Clara was offered a place to stay by a white doctor, who promised to send her to medical school at Howard if she remained. “She thinks she’s staying to save her community,” Chambers said. “But what happens when no one comes back?”

A Conversation Across Generations of Women

Swift River is told through three interwoven voices—Diamond, her Auntie Lena, and Clara—separated by time, space, and silence. Chambers said the decision to write a multi-voiced, epistolary novel wasn’t intentional at first.

“If someone had told me I was writing a first-person, multi-perspective, present-tense novel told in letters, I would have run screaming in horror,” she joked.

But as the story progressed, she realized each character answered a need: Diamond’s voice captured urgency and longing; Lena’s letters grounded her in family; Clara’s voice revealed the buried past.

Originally, Chambers said, she had given Diamond’s father a voice in the manuscript—but ultimately removed it after feedback from novelist Victor LaValle, a previous Gaines Award winner and her thesis advisor. LaValle encouraged her to focus on the voices that had fully emerged. In the end, the father remained present through absence. He is haunting the story rather than speaking in it, she said.

“This is a women’s story,” Chambers said. “These are three women speaking across time like ancestral whispers.”

Honoring Gaines’s Gaze

The Ernest J. Gaines Award, now in its 18th year, was established to honor the legacy of the Louisiana author whose fiction is deeply rooted and often set in rural Black Southern communities. His writings have left an indelible mark on American literature. The prize has recognized writers including Aaliyah Bilal, Jacinda Townsend, Nathan Harris, Ladee Hubbard, T. Geronimo Johnson, Olympia Vernon, and LaValle.

Chambers joins that lineage with a novel that’s already drawn national recognition. Swift River was selected as a Read with Jenna Book Club pick, won the Barnes & Noble Discover Prize, and is longlisted for the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction.

For the community readers in Baton Rouge, the evening was as much about literary promise as it was about literary continuity. Through Swift River, Chambers has extended a conversation Gaines began: about history, about Black life in forgotten towns, and about the dignity of ordinary voices long left out of the archive.

“I believe my ancestors were speaking through me,” Chambers said, reflecting on the process of writing. “There was a conversation happening.”

On this night, that conversation continued. On Tuesday night, that conversation continued and it continues as more readers discuss Essie Chambers' Swift River.

By Candace J. Semien, Jozef Syndicate reporter